I’m leaving you, Limehouse. My beloved Crimehouse. I’m off to Plaistow, where Dad worked in improbably tall buildings and where Helvetica signs told you what to do in the lift, and where Helvetica signs told you what not to do in the lift. It’s where Grandad brought up mum, and where she took us on never-ending Saturdays down never-ending Green Street with its thousands of stalls of the same itchy fabric and disgusting looking vegetables, and lemons, oranges, limes, a reprieve coming only in the emphatic matte and much more unfortunate lime and orange of Percy Ingle. A glass of milk, a doughnut halved. Don’t tell Sean it’s raspberry, he thinks it’s strawberry and hates raspberry. I am leaving you, Limehouse. Slimehouse. Grimehouse. Timehouse.

I have tried everything in my power to become a millionaire so that I can stay with you. I’ve tried running a free short fiction magazine, and I try to turn up at work on time. I go to your Ladbrokes. – you know the one by the Ladbrokes? – and I try to win a house in there. And I save money on your street when you ask me if I smoke weed bruv. I don’t smoke weed bruv. Between me and you, it makes me sleepy. And to be perfectly honest, Limehouse, you shouldn’t smoke weed bruv either. It makes you lazy and you won’t see what’s going on around you. This is Chinatown, Limehouse. Remember that? You could’ve been selling Dim Sum to German families with immaculate trainers, but you were in an Opium den, and Soho did it for you.

Don’t let them take it from you, Limehouse. Make them share it.

We’re not so different from the fascists, Limehouse. That’s the truth of it. We hate change. That is to say change causes discomfort. The fascists were greedy. They didn’t want to share. If you don’t go halves, you’ll lose it whole. The fascists posted shit through the letterbox of change, and it might’ve worked, if they’d been willing to share. But they didn’t want to share. I’ve been thinking about what we can do. Wondering if we could piss on the Estate Agents that tell you that there’s a good side to you and a bad side to you and right down the middle runs Commercial Road. It’s a mean thing to say about you, Limehouse, and I’ve got your back. But no… we’re not so different from the fascists. We don’t like change. We’re just less punchy. And we don’t batter kids under the railway bridge. Instead, we snipe at the beards, and we snipe often.

I know what you’re thinking, Limehouse. You think I’m one of them, with my beard and my too-short trousers. But Limehouse, we’re cousins. I’m from one town over. It’s got a worse rep than you. Its chief export is FGM, and, anyway, I’m heading back there. But I do blame myself. I was the crack in the dam. Can’t tell myself that because I’m from here I’ve got a right to wear too-short trousers on your pavement.

Pavement. Keep your tramps, Limehouse. What happened to that bus stop crew that used to hang out by the kebabish? If the Home Counties types were a flock of birds coming to peck your crops, the bus stop crew were the scarecrows. When they swoop in to prospect the land, they do it with mummy because your deposits and admin fees are not cheap, Limehouse. Mummy sees the scarescrows and she says, “Honestly, Starling, darling, will you not even consider Islington?”

Keep your tramps.

Feeling a bit nervous, actually, Limehouse. I don’t get cut up too easily, but every time I think of you I get a lump in my throat. I don’t know why I get like this. You’re just a place. I love your people. I do. They’re just as annoying as everyone else, but they don’t speak my language, so I don’t have to listen to them. I’m going to miss standing in your street and fixing tight eyes on newcomers. I’m worried I’m going to do something stupid, like cry. When the van comes for us, I might chain myself to your mortar, chuck rocks at riot police, throw away the fob, kiss your spit-puddles. I want to cut your grass and keep it in a locket. It’s not like other grass. It’s barely green. Even in summer it doesn’t smell alive. It stinks. Feeling a bit choked up, actually, Limehouse. I remember sitting on your Cable Street and thinking it was all over. Five years on and married. I remember when I killed a mouse in your bath. I remember coffee good and coffee bad. I remember comedowns and paper rounds, the afrobeat sounds of men dressed like clowns outside African weddings and the elegance of Asian weddings and walking in the road because they don’t give me no room outside the Troxy. No room to walk and I was OK with that, because, Limehouse, you’ve got my kind of people. The kind of people that don’t talk to me. Not really. Other than to ask if I smoke weed bruv or for change. They always ask for change. But it’s not what they really want, Limehouse. None of us want it.

Oh, my Limehouse. Do you think silly of me? Don’t tell Abdi and his dog. Don’t tell the distant grumbles of planes and trains. Don’t tell Sylvia and the caffeine Poles. Don’t tell the eggs benedicts. Don’t tell my one-legged landlord, Captain Most People Are Coming Home Buying Eating Food No Need For Oven. Don’t tell the discarded Rubicon cans and chicken bones in my stairwell that, in autumn light, with the right amount of eye unfastening are breathtaking.

I probably will cry. How many of us have you seen come and go? How many of us cried? You’re tidal without a wave. You are Limehouse, sublimehouse, mainly sub-lethouse. What a timehouse. And I’ll miss you in Plaistow, where Dad worked in improbably tall buildings and where Helvetica signs told you what to do in the lift and where Helvetica signs told you what not to do in the lift. And I’ll miss you. You’re perfect. Don’t change.

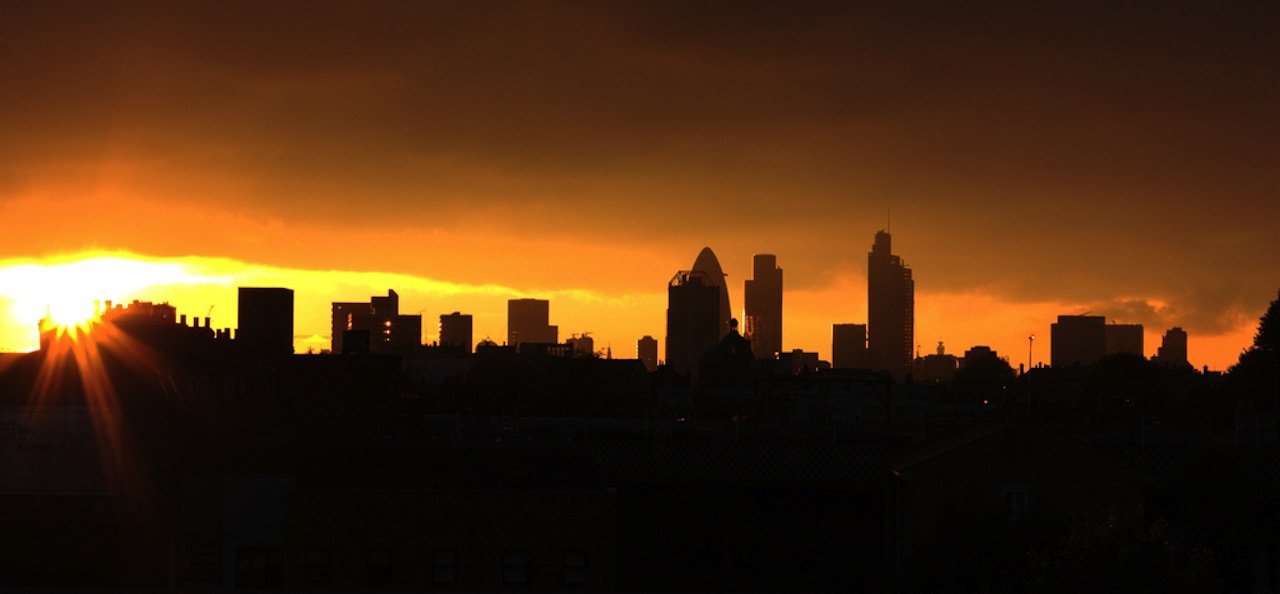

Cover image courtesy of Colm Linehan via Flickr

Sean Preston is the editor of Open Pen Magazine, an ‘open literature’ magazine that has been called “unpretentious, edgy, and utterly readable,” by author and broadcaster N Quentin Woolf. He is a thing-maker for record label Ninja Tune, and retired professional wrestler. He lives in East London, by the Docks, where he battles bravely against doing things, and now and again writes.